How Italian Design Conquered The World

Masters in every fashionable industry that counts, the Italians seem to have it all. Art from Da Vinci, sofas by Citterio and an elusive sense of style the rest of the world could once only dream of attaining. Coveted and incorporated into luxury homes in every corner of the globe, Italy’s long lineage of design heroes have established this passionate nation as a world-leading laboratory for new design ideas. But what is it about the Italian culture that provokes such intense displays of creativity?

Nowadays, Made in Italy furniture enjoys a unique kind of celebrity, setting a global high bar for interior excellence, the equivalent of donning a perfectly tailored Armani suit or the metallic scream of a highly tuned Ferrari. It’s curious then that unlike their Scandinavian counterparts, a consensus on what actually constitutes Italian design still prompts lively debate among scholars.

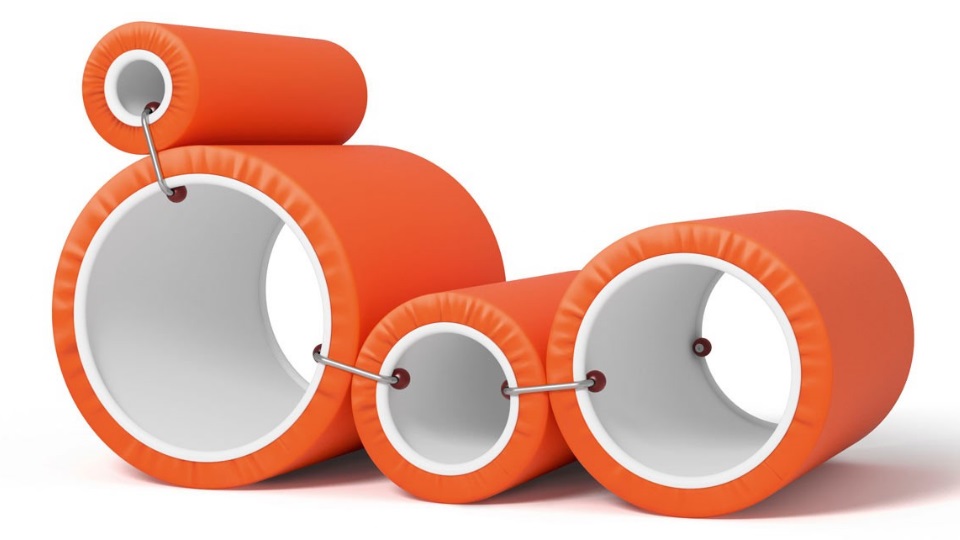

While the Danes and Swedes generally conform to a distinct minimalist aesthetic, luxury Italian furniture can be glamorous or architectural, eclectic or opulent. We see this evidenced year on year in the diverse collections at the Milan Furniture Fair. Is the essence of Italian design reverent wood craftsmanship from Porada? Or perhaps, a modern armchair by Cappellini – vibrant, experimental and daring? But then where does that leave the contemporary favourites, Cassina or B&B Italia? The best answer when trying to conceptualise the thorny issue of national design is, of course, all of the above. Italian design is unique precisely because of this diverse artistic sentiment which in inseparable from the distinct regionalism of its roots.

Giovanni Innella of the Advanced Institute of Industry Technology describes how “design is not an independent force but a product of the political economic context that generates it”. When Italy was first formed in 1871, the city-states that preceded the union retained much of their distinct identities and crafts. Even today, the vestiges of this regional pride exert a strong pull over the people of Italy; Italians from Rome are Roman first and Italian second. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, when the ruling elite began to move south in their droves that competitive collaboration across regional lines would begin to take place. As the fashionable upper classes built glorious villas across slumbering hills and fertile farmlands, they left in their wake small villages of high quality craftsman who had travelled to furnish these decadent homes with luxury bespoke furniture. In this quiet region halfway between Lake Como and Milan, a kaleidoscope of talent emerged, pooling together centuries of regional knowledge to create a design culture that was infinitely greater than the sum of its parts.

One major protagonist to emerge from this breeding ground of innovation was Gio Ponti. His search for new design frontiers, both physical and ideological was motivated by a deep rooted dissatisfaction with convention and an ardent need to advance the future of Italian design beyond what he and his contemporaries saw as the outdated style of neoclassicism. Throughout his illustrious career, Ponti would produce hundreds of fantastical designs for over 120 different companies, with the majority of his classics being manufactured by Molteni & C.

He sought to radically overhaul all aspects of design, from architecture to graphic design right the way through modern furniture, unifying the different artistic operations into a single experience that was able to “transform the face of the environment in which we live and create a new style.” He was successful on every count, and whether it was the acrobatic proportions of the D.552.2 Coffee Table or the Pirelli Tower skyscraper, Gio Ponti set a precedent for outstanding interdisciplinary design across every facet of Italian society.

In the decades that followed, Made in Italy would become synonymous not only with phenomenal design and production but also for emphasising the importance of everyday design. As disposable income grew during the boom of the post-war years, interest in house hold systems thrived, encouraging mass production of all kinds of furniture. From contemporary wardrobes to innovative modern desks, the Italian domestic market grew by a phenomenal 59.8% between the years 1950-1961. The diverse silhouettes of Zanotta’s Sacco Bean Bag, Cassina’s Superlegga and Poltrona Frau’s Club underpinned the era, demonstrating the agility of Italian designers in anticipating and adapting to the public mood.

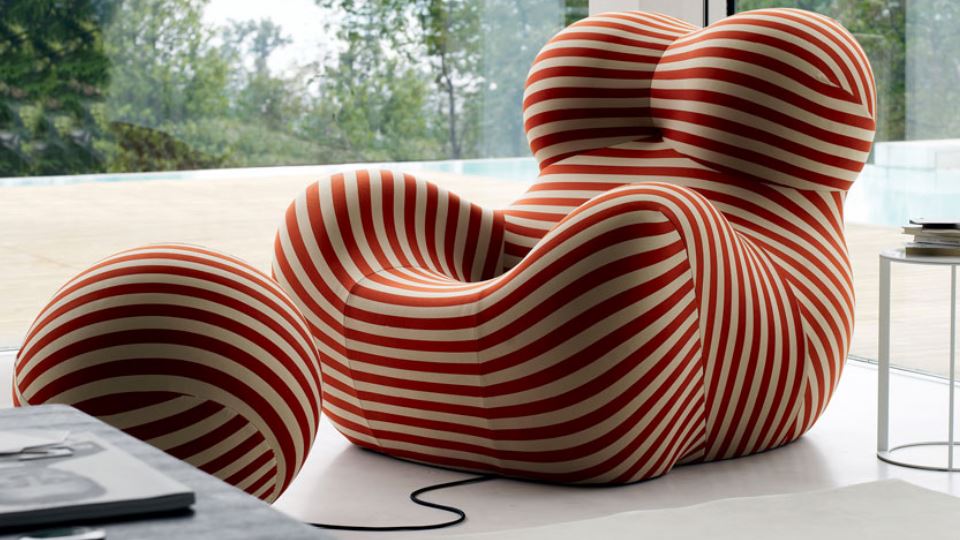

Design in Italy also became an outlet for political commentary, a way of manifesting exuberant ideas that were prohibited by the extreme right wing government of the time. B&B Italia’s UP Series Armchair broke several design and societal barriers with its raucous arrival on the design scene in 1969. Constructed internally from polyurethane foam, the initial model was vacuum packed and compressed into flat boxes and would then self-assemble in front of the client over the course of an hour once opened. Conceptually, the chair is said to encapsulate the female paradox. The buxom figure provides a comfortable womb for the user but remains shackled to the floor by the ottoman in the shape of a ball and chain, positing an interrogation of the role of motherhood in society.

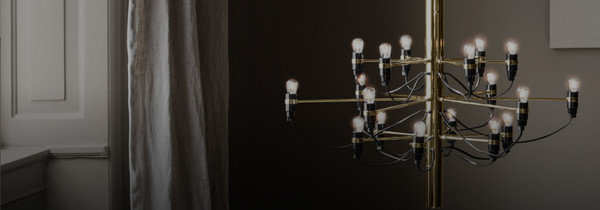

Achille Castiglioni also garnered international acclaim for his ability to re-design existing objects with new, ironic socio-cultural references while still maintaining the elegant appeal associated with Italian design. The iconic Arco Floor Lamp took on the banality of 20th century street lighting while the Mezzadro Stool made for a funky addition to the colourful interiors of the 1970s.

Creative divergences emerged in all methods of manufacturing, and as big name brands like Kartell and Cassina opened themselves to the possibilities of working with outside designers, artisan design took on a whole new global profile. Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand’s innovative collection of luxury chairs and modern chaise longues, initially designed in 1928, rocketed to stratospheric success after partnering with Cassina in 1965.

This spirit of collaboration endured and small Italian design firms began to welcome international designers as honorary members of the Made in Italy design family. Paola Antonelli, one of the R&D Directors at the MOMA Museum in New York writes of how “when designers move to Italy – some for long periods, others permanently – and begin to truly enjoy the work experience and be inspired by it, their design passport becomes Italian.” From the Campana’s extensive work with Edra to Patricia Urquiola’s gorgeous collaboration with B&B Italia and Moroso, international designers from all regions from the globe gather to find creative ways to enrich Made in Italy design, cultivating a national design movement that is in constant evolution.

Globalisation has enabled this glorious cultural exchange. It’s now possible to see a Cappellini classic in a glamourous high rise in Bangkok or a Scandinavian style loft in Berlin. But it has also inspired a political shift towards protectionism and a mistrust of foreign ideals and principles. In a time where half the world seems to want to double down on tradition and the rest seek the cultural enrichment of a more globalised world, what does the future hold for national design?

Fortunately, design has always existed in a sphere above and beyond the fraught world of politics, offering a place where a hankering for traditional ideas and values can be expressed in more fruitful and eloquent ways. Laurameroni’s daring reinvention of tactile surfaces revisits the techniques of the master craftsman of Brianza, reviving them anew with 21st century technology. It’s a similar story for Reflex Angelo, whose intricate dining tables and chandeliers have revitalised the Venetian tradition of Murano glass for the modern era.

Heritage in Italian design is a great source of pride, a feature to be embraced but not an obstacle to the development of new ideas and collaborations. Italy thus offers a perfect model for how the traditional can be enhanced by the new, without threatening the integrity of the original.

Much of the discontent with contemporary globalisation stems from a culture of disposability that has evolved alongside modern capitalism. The outsourcing of production to the cheapest bidder has established in many cases a working class that feel left behind and forgotten. Veneration for the family ensured that Made in Italy designers never trod down this slippery route, instead favouring local Italian methods and manufacturers for the realisation of his or her work.

B&B Italia’s Edouard Sofa, like all other contemporary modular sofas subsumed under the Made in Italy banner, is designed and meticulously manufactured in Italy under the scrupulous gaze of the professional. This faithful attention paid at all stages of production is the reason that Italian furniture has such unparalleled quality — none of its parts have been outsourced to be produced by the cheapest bidder. Attention to detail and a preference for quality over quantity is perhaps one political takeaway that can be learned from the success of the Made in Italy.

For those concerned about the appropriation of cultural styles, they are forgetting that modern furniture receives new meaning in every country into which they are received. A luxury dining table by Cattelan Italia can obtain totally new context when place in a lush green apartment in Tokyo as opposed to a terracotta villa in Tuscany. We are all improved by our proximity to good design and Chaplins is proud to foster an international design culture in an era of inwards looking politics. In an epoch where world leaders opt for tighter borders and the constructions of walls, Made in Italy design offers a historical framework in which collaboration across cultural divides can reap gorgeous and incomparable rewards.